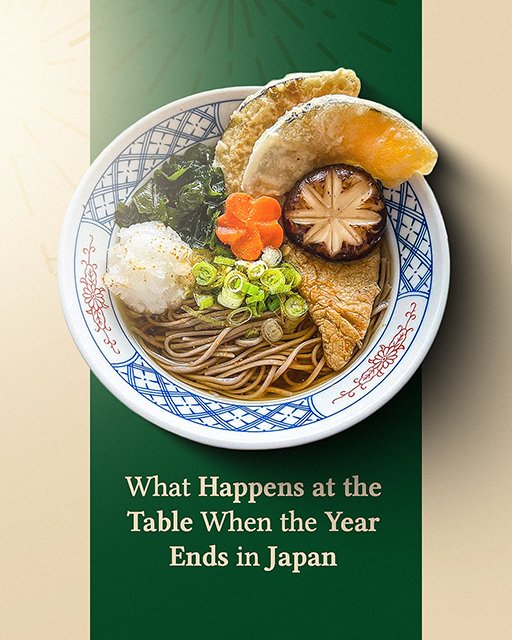

What Happens at the Table When the Year Ends in Japan

In fact, the end of the year in Japan doesn’t come with loud countdowns or late-night parties. Instead, it arrives quietly, through habits, food, and small rituals that help people close one chapter before opening the next.

From the night of 31 December to the first day of January, what people eat is deeply connected to meaning, intention, and gratitude.

31 December: Letting the Year Go

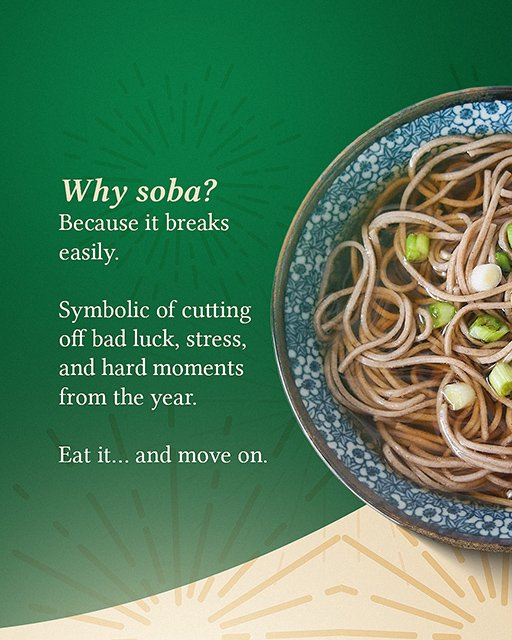

On New Year’s Eve, there’s one dish you’ll find in many homes: Toshikoshi Soba (年越しそば).

Basically, these long buckwheat noodles are eaten to mark the crossing from one year to the next. The idea is simple but powerful — the noodles are long, symbolising longevity, but easy to cut, representing the act of leaving behind the difficulties and stress of the past year.

Therefore, eating Toshikoshi Soba is a quiet way of saying, “This year is done. Let’s move forward.”

Ultimately, it’s usually a simple, warm meal. Nothing fancy. Just enough to close the year calmly.

Food with Meaning, Not Excess

Moreover, in Japan, end-of-year food isn’t about indulgence. Rather, it’s about reflection.

In other words, the focus is not on eating a lot, but on eating with purpose — choosing dishes that carry wishes for health, peace, and continuity. As a result, this mindset continues into the new year.

1 January: Opening the Year Gently

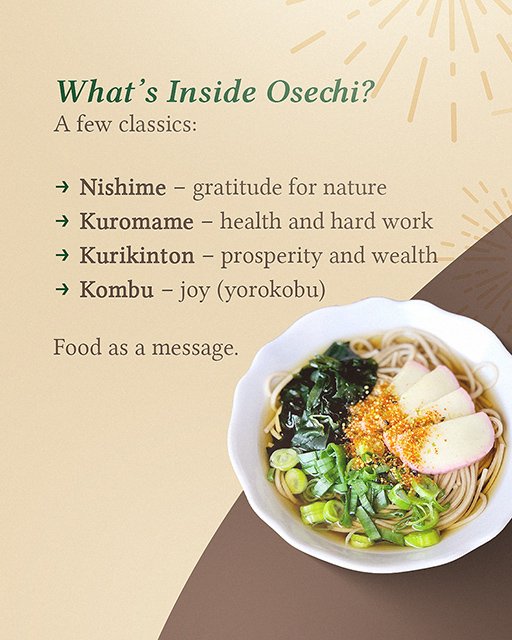

Then, New Year’s Day begins with… Osechi Ryōri (おせち料理).

Osechi is a collection of small dishes, beautifully arranged in layered boxes. Significantly, each item has a meaning and a wish attached to it, making the meal feel more like a message than a feast.

For instance, some traditional examples include:

Kuromame for health and diligence;

Kombu to symbolise joy;

Kurikinton to wish for prosperity.

Everything is prepared in advance, so no one has to cook on the first day of the year. Thus, January 1st is meant to be slow, calm, and shared.

Why Everything Is Prepared Beforehand

Traditionally, cooking on New Year’s Day was avoided.

The main idea was to give both people and kitchens a rest, thereby allowing families to spend time together without rush or obligation.

Consequently, food becomes something you open and enjoy — not something you need to work for that day.

A Different Way to Mark Time

In conclusion, what’s special about the Japanese way of ending the year isn’t the food itself — it’s the intention behind it.

The year is closed thoughtfully. And the next one begins softly. No pressure to celebrate loudly. Just a moment to pause, give thanks, and start again.

📱 Mobile (Text or Call): +61 480 416 307